West Virginia’s streams are in trouble

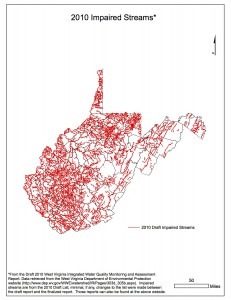

More than 40 percent of West Virginia’s rivers are too polluted to pass simple water-quality safety thresholds. They are too polluted to be safely used for drinking water or recreation, or to support healthy aquatic life.

This is due in large part to pollution from decades of mining. From ongoing pollution from active mountaintop removal mines and toxic discharges from poorly reclaimed mines, the quality streams of West Virginia has never been more degraded.

According to the 2012 Draft West Virginia Integrated Water Quality Monitoring and Assessment Report by the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection, less than a quarter of West Virginia streams fully support all or some of their assessed uses.

The state has failed to collect sufficient data to determine the health of 36 percent of the streams in the state.

In many ways, Appalachian Mountain Advocates has had to take over the job of weak West Virginia state agencies like DEP that have failed to protect the environment. In addition to our legal challenges, we’ve been compiling and mapping West Virginia water quality data over the last several years. The results are a very graphic illustration of just what mining has done to West Virginia’s streams.

Streams can be impaired for a variety of reasons. Raw sewage, agricultural run-off or discharges from industrial plants all contribute to the degradation of stream health. But one of the largest contributors to the poor quality of West Virginia streams is the mining industry.

A brief glance at the map below (download the PDF here) of streams listed as impaired by the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection shows no corner of the state is untouched.

A map showing streams listed by the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection as biologically impaired.

Keep in mind that when the coal industry successfully evades such costs, the expense often falls on the taxpayers of the state.

Streams should be listed as impaired by DEP if they fail to meet state water quality standards for pollution.

However, following passage of SB 562 last year, DEP has stopped listing new biologically impaired streams — streams that can no longer support healthy aquatic life. This new practice is both an incorrect interpretation of SB 562 and a blatant violation of the Clean Water Act.

SB 562 was nothing more than a legislative attempt to protect the coal industry from millions of dollars worth of pollution cleanup costs. It required DEP to develop new thresholds for biological impairment. Rather than use existing thresholds until those new standards are developed, DEP officials simply quit using any threshold at all. This means long delays in cleanup of biologically impaired streams and big savings for DEP’s friends in the coal industry.

If DEP’s contention is that SB 562 constitutes a change to West Virginia’s current water quality standards, it is required to receive the approval of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency prior to implementing that change. To date, EPA has not approved the drastic change being employed by DEP. The agency’s refusal to list biologically impaired streams as impaired is unfounded and illegal. DEP is denying these impaired streams the protection needed to improve the quality of the waters of West Virginia.

In any case, it’s clear that West Virginia’s waters are in trouble and that much of the problem is related to coal mining — both current production and a toxic legacy from past mining. That fact becomes glaringly obvious if you look at water concentrations of specific pollutants directly associated with mining.

If you want to see the link between mountaintop removal mining and selenium pollution, for instance, zoom in on the Google Earth Map here. The red lines indicate streams that the DEP listed in 2010 as violating water quality standards for selenium. The yellow lines indicate streams that Appalachian Mountain Advocates has identified as impaired for selenium based on data we’ve collected. After we submitted this data to DEP, many of the streams that we suggested were added to a DEP draft list of impaired streams.

Wisconsin’s Mining Moratorium Under Attack

Al Gedicks and Dave BlouinWisconsin Governor Scott Walker and the mining industry have begun a major lobbying effort to overturn Wisconsin’s landmark Mining Moratorium Law. The law, also known as Wisconsin’s “Prove it First” law, was developed to address the problem of acid mine drainage from metallic sulfide mining.

The Flambeau Mine near Ladysmith, Wisconsin before reclamation. The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources recently completed an investigation of water quality at the Flambeau Mine site and recommended that “Stream C,” a tributary of the Flambeau River into which Flambeau Mining Company has been discharging polluted runoff from the mine site since 1999, be included on its list of “impaired waters” for 2012 for “acute aquatic toxicity” caused by copper and zinc.

Tim Sullivan, chairman of the Wisconsin Mining Association, is leading the effort to repeal the law. Sullivan is the governor’s special assistant for business and workforce development and a past director of the National Mining Association. He is a former president, CEO and director of Bucyrus International, the largest mining machinery company in the world, now owned by Caterpillar Corporation. He recently told a Wisconsin Senate Mining Committee that Wisconsin’s Mining Moratorium was an obstacle to new sulfide mine proposals, including Aquila Resources’ gold and copper sulfide deposits in Marathon and Taylor counties in north central Wisconsin.

Mining lobbyists have cited the “success” of the partially-reclaimed Flambeau metallic sulfide mine in Ladysmith, Wisconsin, which Kennecott/Rio Tinto operated from 1993-97, as a reason for repealing “Prove it First” legislation. However, there is no scientific evidence to support such claims.

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) recently completed an investigation of water quality at the Flambeau Mine site and recommended that “Stream C,” a tributary of the Flambeau River into which Flambeau Mining Company (FMC) has been discharging polluted runoff from the mine site since 1999, be included on its list of “impaired waters” for 2012 for “acute aquatic toxicity” caused by copper and zinc. These illegal discharges of toxic metals are why U.S. District Judge Barbara Crabb recently ruled that FMC violated the Clean Water Act on numerous counts.

Wisconsin is now under a well-funded mining industry attack on the grassroots environmental, sportfishing and tribal movement which mobilized tens of thousands of Wisconsin citizens to successfully oppose Exxon’s destructive Crandon mine at the headwaters of the Wolf River and enact Wisconsin’s landmark Mining Moratorium Law. That citizen movement also supported the sovereign right of the Mole Lake Ojibwe Tribe to protect itself from any mining pollution upstream from the tribe’s sacred wild rice beds. In 2003, BHP Billiton admitted defeat of the Crandon mine project and sold the mineral rights to the zinc and copper deposit to the Mole Lake Ojibwe and the Forest County Potawatomi Tribe.

Veterans of the 28-year Crandon mine battle were among those who mobilized public opinion against Gogebic Taconite’s (GTac) proposal for a giant open pit iron mine in the headwaters of the Bad River watershed adjacent to the sacred wild rice beds of the Bad River Ojibwe Tribe on the shore of Lake Superior. GTac wrote legislation that exempted itself from critical environmental protections and excluded the public and the tribes from the permitting process. Strong criticism of the Iron Mining bill led to its defeat by one vote in the Wisconsin Senate last spring.

With new GOP majorities in the Wisconsin Legislature, Governor Walker, along with the WMA and Wisconsin Manufacturers and Commerce, has made passage of the Iron Mining Bill and repeal of Wisconsin’s Mining Moratorium Law their top legislative priority in 2013.

Many of the new Republican legislators are unfamiliar with the Crandon mine conflict and the ongoing pollution at the closed Flambeau mine. How else can one explain the disregard for the sovereign rights of the Bad River Ojibwe Tribe, whose sacred wild rice beds and way of life are threatened by mining pollution from GTac’s proposed open pit mine?

The tribe has sovereign authority, under the Clean Water Act, to protect its wild rice from mining pollution. They also have the right to be consulted about any legislation that would affect their treaty rights. So far, these rights have been ignored. Legislators rushing to accommodate the wishes of powerful corporate actors may be in for a painful reminder about the power of engaged citizens and tribes.

Uranium Mine by Pine Ridge Nearing Approval

State to rule Oct. 31 on request

Thursday, October 18, 2012The following story was written and reported by Talli Nauman, Native Sun News Health & Environment Editor. All content © Native Sun News.

By Talli Nauman, Native Sun News

Health & Environment Editor PIERRE — The South Dakota Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) announced Friday, Oct. 12, that Powertech (USA) Inc. has submitted four applications — for a large-scale mine permit, groundwater discharge plan and two water right permits — upstream from the Pine Ridge Reservation. The state is reviewing them to decide on the first uranium underground injection — or in-situ leach (ISL) — mine proposed for South Dakota.

“Given the time it will take to determine that the applications are complete, time to conduct technical reviews of the completed applications and the public comment periods, it will likely be sometime next spring before the Powertech applications are heard before the state boards,” said DENR Secretary Steve Pirner.

However, department staff are currently reviewing Powertech’s large-scale mine permit application for procedural completeness and will notify Powertech by Oct. 31 “whether the application is complete or if additional information is required,” DENR said in a written statement. Powertech submitted the large-scale mine application on Oct. 1 for its proposed Dewey-Burdock Project in the state’s southwestern counties of Custer and Fall River, adjacent to the Pine Ridge Reservation. Canadian Powertech Uranium Corp., parent company of Denver-based Powertech (USA) Inc., considers the 10,850-acre permit area on 18,000 acres of the Black Hills along the Cheyenne River to be a “flagship” site, with as much as 10.8 million pounds of uranium still left since its discovery in the area in the 1950s. Almost 20-percent owned by the Belgian corporation Synatom, Powertech hopes to sell uranium to that and other nuclear power interests. It plans to use injection wells to pump groundwater mixed with oxygen and carbon dioxide into ore deposits to dissolve uranium. So-called production wells then would be used to pump the uranium-laden fluids to the surface for recovery. The fluids would be processed at the mine site to extract and concentrate the uranium. After removal of the radioactive mineral, groundwater would be treated to meet standards.

Wastewater would be disposed by either injection wells federally permitted through the Environmental Protection Agency or by land application regulated through a DENR Ground Water Discharge Plan. Powertech has applied for both. It also has Nuclear Regulatory Commission approval pending in a process where tribal governments can make or break the deal. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission is preparing a Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS) and Safety Evaluation Report (SER) for the project. It has accepted Powertech’s data for extracting uranium from the Inyan Kara group of host sandstones in the Southern Black Hills, the company announced Aug. 1. Powertech said in a written statement that it expects the SER to be completed by the end of October.

“Through several years of baseline data gathering, drilling of numerous additional confirmation drill holes, testing of the Inyan Kara aquifer, and subsequent analysis of all the collected data, the character of the Dewey-Burdock Project has been thoroughly outlined with sufficient detail for the NRC to undertake its comprehensive review,” the company stated. “We are very pleased that we have reached this milestone,” Powertech President Richard Clement told the media. “We look forward to completing the entire permitting process to begin operations on one of the best undeveloped uranium deposits known in the U.S.” However, tribal governments have delayed the project by stalling a cultural property survey proposal and detailed cost estimates requested by the NRC.

On Sept. 18, NRC Environmental Review Branch Chief Kevin Hsueh sent tribes a letter stating: “It is imperative that we proceed with identifying any National Historic Preservation Act-eligible properties before the end of the 2012 field season (i.e., in the fall 2012). The staff respectfully requests that the participating tribes designate a preferred contractor to complete a cultural resources survey on their behalf and provide NRC with a written proposal with cost estimate based on the 2,637-acre area that may be disturbed during the first phase of the proposed Dewey Burdock project.” He addressed the letter to the Crow Nation, Oglala Sioux Tribe, Northern Cheyenne Tribe, Rosebud Sioux Tribe, Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate, Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and Yankton Sioux Tribe, who participated in a project meeting with NRC representative Jean Trefethen and NRC contractor Randy Withrow in Bismarck, N.D., on Sept. 5. He requested the response by October.

Since the first formal Section 106 consultation meeting with the tribes seven months ago, Powertech presented a draft Scope of Work in May, and the tribes responded with a revised version on Sept. 3. In his letter, Hsueh said the tribes must complete a “final eligibility report” no later than 60 days following completion of the field survey. The report must provide the location of all identified historic preservation sites, a description of where each site is located in relationship to areas that will be directly impacted by planned operations, and recommendations regarding the eligibility of each site for listing in the National Register of Historic Places.

The NRC wants the tribes to contract with Powertech rather than the NRC for this work. But since the first consultation meeting, tribal representatives have refused.

Originally, Powertech also faced a state permitting process for the underground injection, as a result of rules established through a laborious public planning process carried out during the past five years. However, after failing twice to gain DENR approval of the permit application, company representatives last year convinced the 2011 Legislature that state oversight duplicated EPA’s, achieving a statute that relieved the department of regulatory and public information access duties.

The South Dakota Alliance for Progress alleged that the move to shelve state supervision was an end-run around the permit process. “If there is ever a more cynical method of bypassing legitimate governmental oversight, we fail to see it,” the Rapid City-based organization said in a written declaration. When Native American Sen. Jim Bradford, D-Pine Ridge, and other legislators tried to repeal the legislation this year, they failed.

They were responding to Lakota activists, as well as non-Indian constituents, who like Owe Aku founder Debra White Plume, questioned, “Why make it easier for corporations to damage our environment?”

Read all the above click here: http://www.ienearth.org/category/native-energy/mining/