Comments: Uranium Mill requests to run Alternate Feed during down time to process uranium! The profit is higher for Alternate Feed !

Uranium Mill and Disposal Facilities:

Dawn Mining Corporation Midnite Mine Alternate Feed Request

- White Mesa Uranium Mill - RML UT1900479 April 27, 2011

Request to Amend Radioactive Materials License to Allow Processing of Alternate Feed Materials from Dawn Mining Company's Midnite Mine Water Treatment Plant ("WTP") Response to January 22, 2013 and January 23, 2013 Utah Division of Radiation Control Requests for Information (06/14/13)

- Radioactive Material License (RML) Number UT 1900479Additional Request for Information on Proposed Alternate Feed Amendment Request - Material from Dawn Mining Company (01/23/13)

- Radioactive Material License (RML) Number UT 1900479Request for Information on Proposed Alternate Feed Material From Dawn Mining (01/22/13)

- State of Utah Radioactive Material License No. UT 1900479 April 27,2011 Amendment Request to Process an Alternate Feed Material from Dawn Mining Company Transmittal of Supplementary Information (12/05/12)

- Midnite Mine - Water Treatment Plant Sludge

(11/08/12)

- Amendment Request to Process an Alternate Feed Material License No. UT1900479Amendment Request to Process an Alternate Feed Material (the "Uranium Material") at White Mesa Mill (the "Mill") from Dawn Mining Corporation ("DMC") Midnite Mine

State of Utah Radioactive Material License No. UT1900479 (04/27/11)

Uranium Mill and Disposal Facilities: Sequoyah Fuels Corporation Alternate Feed Request

- Comments from Review of "Application by Denison Mines (USA) Corp ('Denison') for an amendment to State of Utah Radioactive Materials License No 1900479

Comments from Review of "Application by Denison Mines (USA) Corp ('Denison') for an amendment to State of Utah Radioactive Materials License No 1900479 for the White Mesa Uranium mill (the 'Mill') to authorize processing of Sequoyah Fuels Corporation, Inc ('SFC') alternate feed material ('Uranium Material')" dated December 15, 2011 (12/04/12)

- Application by Denison Mines (USA) Corp. ("Denison") for an amendment to State of Utah Radioactive Materials License No. 1900479

Application by Denison Mines (USA) Corp. ("Denison") for an amendment to State of Utah Radioactive Materials License No. 1900479 for the White Mesa Uranium Mill (the Mill") to authorize processing of Sequoyah Fuels Corporation, Inc. ("SFC") alternate feed material (the "Uranium Material") (12/15/11)

Uranium mill or dump?

- by Rosemary Winters

Locals hope to stop a Utah mill from finding new work

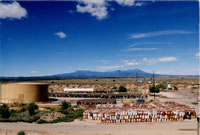

WHITE MESA, UTAH — If you blink on the drive between Blanding and Bluff, you might miss the White Mesa Ute Reservation. From Highway 191, this small community of 300 Ute Mountain Utes is marked by a gas station, a Mormon ward house and a smattering of trailer homes. But if your window is rolled down, you could catch a whiff of the Utes’ neighbor. When it’s running, the International Uranium Corporation’s mill saturates the air with the stench of sulfur.The mill — one of only two surviving uranium mills in the country — has switched to a controversial practice in order to stay alive in a depressed uranium market. Instead of processing uranium ore, which is not currently mined in the U.S. because prices are so low, the mill "recycles" mine tailings, contaminated soils and Manhattan Project waste — collectively known as "alternate feed" — to glean any remnants of uranium. It then sells the concentrated, purified uranium, called yellowcake, to nuclear power plants.

The leftover alternate feed, piled out in the open, uncovered, is nasty stuff. Dust sometimes blows off the piles, and the mill’s smokestacks and tailings piles emit radon and thoron gases, sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides. Although those emissions meet national air-quality standards, the toxins still pose long-term risks of cancer and respiratory disease, according to the U.S. Department of Health.

For 53-year-old Ute Mountain Ute Thelma Whiskers, who lives in a small house separated from the mill by only a four-mile stretch of cheatgrass and juniper trees, it’s galling that the mill was built on top of more than 200 Ute, Navajo and Anasazi ceremonial and burial sites.

But even more galling is the fact that the mill may be nothing more than a poorly disguised waste dump. The mill extracts only minute amounts of uranium from the alternate feed, and makes its money from charging recycling fees, not producing uranium. "The uranium values in the feed material are very low," says Loren Morton, a hydrogeologist with the Utah Division of Radiation Control. "It’s the recycling fee that makes the economics (viable)."

Drumming up business

The Energy Fuels Corporation opened the White Mesa Mill in 1980, and, floundering in bankruptcy, sold it to the International Uranium Corporation in 1997. With the uranium industry hanging by a thread, IUC turned to alternate feed for new business, touting its recycling services as an environmentally superior alternative to direct disposal. Some yellowcake is extracted, but most of the material winds up in the mill’s outdoor disposal cells.In 1997, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) granted the company an amendment to its license so it could accept uranium tailings from a former mill in Tonawanda, New York. In 1998, the state of Utah appealed that amendment, arguing that the NRC should set a minimum concentration of uranium content for a waste source in order for it to be deemed alternate feed.

The state lost the appeal, and International Uranium raked in more than $4 million in fees for processing the Tonawanda material, which contained less than $600,000 worth of uranium, according to the state. The mill has to gain a license amendment for every new contract, but NRC regulation remains lax: Anything with trace amounts of uranium can be considered alternate feed. And since 1997, International Uranium has processed more than 300,000 tons of radioactive waste from California, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Illinois and Canada.

The mill produces about 1 pound of uranium for every ton of alternate feed it processes, according to Ken Miyoshi, the manager of the White Mesa Mill. It takes years to stockpile enough alternate feed for the mill to operate: The mill was on standby from 1999 to 2002, and then ran from June 2002 to May 2003.

Miyoshi says processing alternate feed is a way to keep the mill running until uranium prices rebound, and that the company pumps money into the local community through jobs and taxes. But the economic benefits for the Ute Mountain Ute tribe are insignificant, says Tom Rice, the tribe’s environmental director. Only two or three of the 50 workers needed by the mill when it’s running are Utes, and the temporary jobs only pay about $8 an hour. And, he says, the mill’s proximity limits the tribe’s ability to create a tourist economy.