Struggling to reclaim their health and land after decades of uranium mining, the Navajos find a strong advocate at Tufts

But there were dangers, too. Flash floods would fill the arroyos, and children could fall in and drown. And one time his sister brought home a new pet in a Dixie cup—a scorpion—that made their mother scream.

It wasn’t until he traveled back to the reservation at the age of thirty-two that Brugge realized a far greater danger had lurked all around him: the sacred land of the Navajos—which had once supplied America’s nuclear weapons program—silently throbs with radiation.

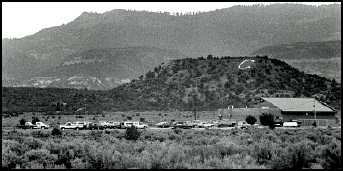

From 1944 to 1986, nearly four million tons of uranium ore was extracted from the reservation, an area the size of West Virginia that spans northeastern Arizona and parts of New Mexico and Utah.

When demand for uranium dried up at the end of the Cold War, the mining companies simply abandoned the roughly thirteen hundred mines, leaving behind radioactive waste piles known as uranium tailings. Navajos inhaled radioactive dust and drank water contaminated with uranium, arsenic, and other heavy metals, and the cancer death rate there doubled, according to Indian Health Service data.

Uranium ore has all these things in it—radium, thorium, uranium,” Brugge says. He explains that the ore’s deadly properties are released only when it is dug up. “Radium decays into radon, and radon decays into a whole series of radioactive isotopes very quickly that are giving off all these alpha particles. When these particles lodge in your lung, that is a disaster for your health. They cause lung cancer.”

Today, Brugge is a leading expert on uranium, and consults on nuclear policy issues worldwide. But he also devotes much of his time to the ravaged homeland of the Navajo people, intent on bringing about some measure of what he calls environmental justice. He presses for health studies and works with federal and tribal organizations on legislation to clean up mine waste and compensate miners who get sick from uranium. He shares both his scientific expertise and his knowledge of the place where he grew up, a place where people can be mistrustful of outsiders and skeptical of government interference.

Read more:

http://www.tufts.edu/alumni/magazine/winter2012/features/tainted.html